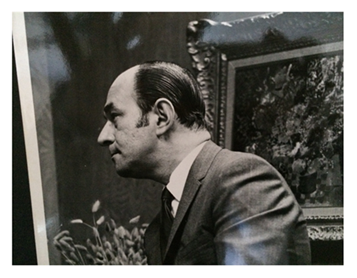

By Bruce Dolin

My name is Bruce and my dad was Dave. We buried him on December 3, 2012. It was a warm and drizzly Chicago morning, mud sticking to my leather boots, and a moment I had anticipated with dread and curiosity for nearly fifty years.

My name is Bruce and my dad was Dave. We buried him on December 3, 2012. It was a warm and drizzly Chicago morning, mud sticking to my leather boots, and a moment I had anticipated with dread and curiosity for nearly fifty years.

In my first memory of my father I am wearing a sailor suit. I am two, I am behind the bars of my crib, and I am crying with rage and indignation.

In my second memory of my father, I am walking with my hands in my pockets and he insists I take them out. I do not, and then I trip and cut my lip on a nail on my Bubby’s brass transom. Every pass of the doctor’s needle through my flesh whispers, “I told you so, I told you so, I told you so.”

At four, I realize that we all die — and I suffer my first panic attack, initiation into existential dread. My father and his Mad Men sophisticated friends laugh and laugh at the cuteness of my precocious neuroticism, as I sit on my mother’s lap thinking, “It will happen to all of you before it happens to me…”

And then I have the dream about my father that has haunted me all my life: He is wearing boxers and a French cuffed button down, busy in the back yard, shoving an exact half-dressed replica of himself into a grave. There are multiple apparitions of him already in the pit, a repeating pattern like his doodles, like his OCD, like my looping thoughts — a long line of dad facsimiles in boxers and French cuffs, each waiting to push the one in front into the earth as a trail of same selves extends behind, ready to press the grim business forward.

At thirteen I realize that I do not want to have a bar mitzvah and I make my case with reason and balance, chiefly an attack upon what I view as the hypocrisy of my father’s temple, a place where one dresses up to be seen, a boring and false place where God seems unlikely to want to hang around, wanting instead to get right out of there and take a walk, maybe steal some candy from the White Hen Pantry, maybe find something more fun to pursue.

My father, lounging in his bed in his boxers and French cuff shirt, listens to my plea and then responds: “My father got bar mitzvahed and hated it, I got bar mitzvahed and hated it, and you are going to get bar mitzvahed and hate it.”

Sometimes my father spoiled me, like the day he took me to Brooks Brothers for the first time when I was six, and he bought me a snazzy camel’s hair coat with matching cap on a blustery Chicago afternoon. Sometimes we would go to Navy Pier and get fried shrimp, and we’d eat them salty and oily and steaming from a brown paper sack, as the windows of the Lincoln fogged opaque. Often my brother was there, too, in the tightly closed car, like a breathy boys’ club of forbidden fruit and man-love and leather seats and secrets.

At twenty, my father sat across from me at Jack’s during one summer home from college, a Saturday breakfast, and he passed a thick computer printout across the table. I looked down: rows and rows of stocks and real estate. “What’s this?” I asked. This was before Lost in America and thus it was utterly without irony that my father declared, “This is the nest egg.”

I perused the pages as he continued: “I’m starting a new business. These assets are for your mother when I go, and after her, this is for you and your brother. A new business is risky, and this is the money I will never touch.”

We had never discussed money, not how much he made, not how much things cost. He had said once that he wanted “fuck you” money, which he went on to explain meant “enough money to be able to say ‘fuck you’ to anyone.”

I guess he’d made it. And in the calculus of the mind, of my mind, I said to myself, “You’re going to be rich one day. You can major in film. Fuck the professions. Fuck business school. Take the risk.”

I was halfway through graduate film school when my dad cut me off. The money was gone. He’d slowly siphoned off the nest egg and now he was ashamed and indebted to friends and to banks and to the I.R.S.

My father had long said that he feared becoming Willy Loman, and over the next twenty-five years he performed the same desperate monologue over and over. The gist of it was, “I’m not a young man, I can’t recover like you, you don’t understand.”

So I headed West to another life, another beginning, where Hollywood inspired a need to lie on the floor and breathe deeply, a need to remind myself that leaping onto the palms that seemed so soft below my seventh story window would, in actuality, be sharp and cutting. Hollywood inspired therapy, and therapy inspired the notion that being a psychologist might be a better idea for me than being a writer. I was nearing thirty and wanted to build a future that might be about helping others and about steadiness, and not about picturing myself still in temporary jobs in twenty years time. At breakfast on a bright Sunday on La Cienega Boulevard I told my dad my plan. He said, “I think it’s a big mistake.”

My father confused me, refusing to speak to me for four months after I told him that although I loved him, he also sometimes hurt my feelings. His sulking silent rage took me by surprise. I was thirty-four then and we were walking in the gardens of the Four Seasons in Santa Barbara under a dazzling sun; my cousin had arranged a suite on the occasion of her wedding, luxury to deeply savor when you’re broke and have a newborn and you’re rethinking life as a father yourself.

When I finally afforded a house at forty-two, and by then I was helping my father financially as best I could, he came to see the place and told me, “It’s a nice starter house.”

“You don’t understand,” I replied. “I’ll probably die in this house.”

On his last visit to Los Angeles, a trip where he fell a couple of times, my father casually tossed a soiled Depends into the wastebasket in the bathroom. After he left, the dog brought it out in her teeth, wagging her stubby tail. My wife and boys and I laughed that laugh to keep from crying, but then I cried a little, too, all the same.

In the assisted living facility it seemed they were often playing the Eagles’ song Hotel California as if LA and Chicago were now mingling in some brackish surreal netherworld as, in for a weekend, I watched my dad dribble and drool in the dining room. I brought whiskey one afternoon and we sipped it. As a child, I always brought him his Johnnie Walker Black Label as he washed his face after work, in his boxers and French cuffs. “Promise me you’ll always drink good Scotch,” he would say with a tough-guy smile.

It was the last day of what would turn out to be the last visit that I would see my father alive when my mother turned to him, the man now crumpled and frail in a wheelchair, and she asked him, “What was your favorite time in your life?” My father considered this, in and out of lucidity perhaps, his hands spotted and trembling, his skin like paper, and then he answered, “Right now.”

I spent my fifty-third birthday on holiday beside a beautiful river, black and purple butterflies rising amongst the pines against an azure sky, falling sticks plucked deftly by Zephyr drafts like magic wands, the river holding her secrets as I was crying alone, despondent, because I missed my dad.

I waited a year to fly back to my father, a year for his soul to prepare to really get going, a year for me to get ready to truly let go, a year to arrive at the cemetery – my mother, my brother and myself. But it had snowed all night and we had to search for his gravestone beneath a white veil. We toasted him with the remains of a bottle of Johnnie Walker Blue Label I’d splurged on a year earlier in order to raise a proper glass after the funeral. We drizzled a little on the snow.

I thought 2014 would be my liberation, my time to shine; so far it’s been marked by panic and restless nights. You just don’t know how you’re going to feel or what’s going to happen or what any of it means – these departures, these passages, these tentative transitions. But when asked to write about my father I said “yes” and began writing instead of thinking, and in my own way, hoping that I have honored my father with these words.

Mark Twain said something about thinking your dad is an idiot when you are eighteen and realizing how much he’d learned when you turn twenty-two. Maybe I saw my dad as a bit of a blunderer when he lost his money and his sense of humor along the way, but as I look back at him now, wondering where he is and what he thinks if anything at all, I ask myself if he’s not some sort of Bodhisattva — some enlightened being who’s chief aim is to promote non-suffering. After all, he loved us to the end, quietly, and without his house; showing us the way to lose our money, our ambition, our anxiety; showing us how to die; and maybe if we can finally die, we can also finally live and love, with who we are, in the here and now.

My dad was thirty-four when I was born and I was thirty-four when my first son was born. My dad was eighty-six when he died and I cannot be sure of the pattern, but I feel the eternal footman holding my coat and I shudder just a bit. I may have taken a long time to understand, but I know that my father loved me and that he was proud of who I became. I feel his love now (or indulge in imagining that I do), uncomplicated and untroubled, a love I’d like to live bravely and softly, discovering it everywhere in this world we share.

I love you, Dad.

© Bruce Dolin

Bruce Dolin, Psy.D., is a psychologist practicing in Beverly Hills. He specializes in helping clients with depression, anxiety, relationships, parenting, creativity and the myriad struggles we all face in our quiet quest to relax and enjoy being alive. He is the author of a book, Privilege of Parenting , and a widely respected blog that addresses parenting issues with a highly personal (and literary) touch, PrivilegeofParenting.com. Follow Bruce on Twitter @BruceDolin.

Part 7 in a series on father-son relationships. Read the Mother-Daughter Series here.

You May Also Enjoy

Oh, Bruce. I read this beautiful elegy to your father through tears. It’s a song we hear forever, isn’t it, the call and response chant between ourselves and our parents and our children too, back and forth across generations. All I want is to be able to hear it clearly, always. I think it’s extraordinary that your father answered your question about his favorite time in his life with “right now,” and we should all aspire to that kind of contentment and peace in and with every season of our lives. xox

Thank you for these kind words, Lindsey—here, now, through the ether and with our children. Hugs

Just wanted to let you know that this was beautiful. xo

Hi KW—much appreciated (as I’ve been under the radar lately). XO back at you too!

Beautiful writing and a wonderful tribute to your dad who showed you life.

Thank you Madgew for the kind words 🙂

“My father got bar mitzvahed and hated it, I got bar mitzvahed and hated it, and you are going to get bar mitzvahed and hate it.”

I love it.

Perhaps then today I am a man? A nervous and uncertain man, but nevertheless…

Bruce,

I’ve thought about my father so much lately. In March of this year, it will mark 5 years without him.

Losing my father steered my life in such a different direction.

Reading your essay brought tears to my eyes. Beautiful, courageous, and poignant. Thanks for writing it. I know it took incredible strength.

Hi Rudri, I thought of you when I was writing this, as you had to go through it first and your writing about your dad’s passing moved and inspired me. Thank you for your kind words! Hugs

Bruce, this is so beautiful and sad and honest and real. I am in awe of the way you capture the nuances that exist in all of us. Mostly, this is an essay that my heart hears clearly. I am sorry for your loss and for the hard times that are an inevitable part of grieving. There are so many wonderful lines here. This one struck me:

So I headed West to another life, another beginning, where Hollywood inspired a need to lie on the floor and breathe deeply.

I think of us all lying on the floor and breathing together. Lots of love to you.

Hi Pamela, Actually you’re so much braver than me that I know you inspire a lot of us who cluster around each other’s words and soulful attempts to make our way to quiet and calm and together. Yes, on the floor together—so much better than alone. XO

I love that you can look at all these tender wounds as gifts, at your Dad’s accumulation of losses as a series of spiritual teachings. And perhaps by losing everything, from the “fuck you” money to bowel control, and loving his life in the moment anyway, your dad gave you the greatest gift of all–the realization that although nothing lasts, this brief, far-from-perfect life is precious and beautiful anyway. I’ve missed you Bruce, and all your friends, too — feels like a reunion here! And I’d say you already ARE shining in 2014.

Hi Katrina, You are such an inspiring teacher of this central, and hard to live, hard to stay centered within, loving wisdom of the present moment with all its precious and bittersweet beauty. “Reunion”… I like that idea. Perhaps another LA walk before too long! Hugs

Bruce – nice stuff. Interesting reading, as their are such similarities between us. My kid was born when I was 34, my Dad is still around at 82, he was Bar Mitzvah-ed and was lukewarm about it. I was also Bar Mitzvah-ed and only parts of it were distasteful. We’re just trying to find the answers to life’s persistent questions…

Hi David, Thanks—I think of numbers, patterns… 13, 34, being a kid, becoming a man but you’re still a kid, becoming a dad but you’re still a kid, losing your dad and realizing you’re not a kid anymore, maybe getting old enough to feel like a kid again. All Best Wishes

Hello Bruce. I too cried while reading your beautifully honest and engaged tribute for your Father. I have so many strong emotions of my own Dad’s passing that I am still trying to see through those tears as well, to find out where some sort of truth lies or how it matters now.

Thank you for giving me a bit of insight. For in your story…well…I had the image come to mind of spokes on a wheel leading outward from a central core…that probably doesn’t make any sense now, does it? Just in that we all have our own stories as did they. All coming from Love whether we know it at the time or not…

With my Best Regards from Provence,

Heather

Hi Heather, Thank you so much for your words here. The spokes of a wheel makes perfect, intuitive and loving sense to me. And Provence holds such a numinous and mysterious place in my heart as well, particularly St. Remy and the mysterious strands and spokes that seem to connect in paint, and words, and wind, and light, and food, and love across history and time and states of consciousness. Here’s to softness and kindness even in the midst of bittersweet confusion (p.s. I’m in the midst of roasting a chicken with herbs which had me thinking of France before I read your comment). All Best!

Hi Bruce – As I was reading your piece, my dad called to check in on me and it didn’t feel like a coincidence given all the feelings of complicated love and striving and connection that you evoke here. Your writing here sings and I come away with a picture of a man who tried hard even if he didn’t always succeed in loving and living and providing the way he intended. I suspect many of us would feel lucky to be able to say the same at our own deaths. I know that I feel lucky to call you, his son, his Brooks Brothers coat-wearing, Bar Mitzvahed boy, a friend. With much love, Kristen

Such very kind and encouraging words, Kristen. I too am honored to count on you as a dear friend. Much love back, Bruce