As a mother of two, it’s only natural that I think of my own mother and how she parented. As the years have passed, I’ve come to appreciate the difficult job of raising children, and the ways in which I think my mother did well. I’ve also experienced the stark loneliness of parenting on my own.

Going it alone was the case when my mother was a homemaker, despite being married at the time.

Going it alone was the case when my mother was a homemaker, despite being married at the time.

I tend to feel my mother’s presence (and absence) acutely at the holidays, which is to be expected. This is the season when we wish to bask in the bosom of our loving families, though few of us live the idyllic scenes of household harmony we view on our flat screens and hand-held devices. Instead, even in basically sound relationships, conflicts are magnified, regrets are palpable, and some of us find our mother-daughter realities far from what we once hoped.

Naturally, I feel the void created of my mother’s passing on other occasions as well. But then, I felt her absence when she was very much alive and we were at odds.

Sadly, that state of affairs was our reality for decades.

Mother-Daughter Relationships

Mother-daughter relationships are often characterized by years of contradictions – fierce and protective love, hurtful acting out by both parties, disapproval and competition.

We may also know extraordinary acts of compassion and generosity. But suffice it to say, when our mothers’ better angels are scarce, it can take a lifetime to accept the relationship as we know it, trying to make peace with whatever we have experienced.

Mother-daughter relationships are fascinating fodder, especially as we grow older. We arrive at a near visceral understanding of the daily decisions, the constant compromises, and all the factors that influence our behaviors when we take on the motherhood role. And that role, as we well know, is too often a situation of “damned if you do and damned if you don’t.”

Regardless of the loving or contentious nature of the bond, perhaps we come to a place of greater empathy for our mothers, as I have over the years.

In light of the delicate and fundamental nature of these relationships, I have invited a number of women writers to explore a little piece of their adult understanding of their mothers. I look forward to sharing their memories and lessons, as I can only imagine that we will find a mix of affection, admiration, tenderness, and potentially bitterness, resentment, animus.

Some of us fight difficult parental legacies our entire lives; others bask in the best possible kind of love. Some of us are caring for our mothers now, as they move from midlife into their older years; others enjoy activities together as would close friends.

Some of us have already said our goodbyes. Others will have no opportunity to exchange those farewells in person.

My Mother, Myself

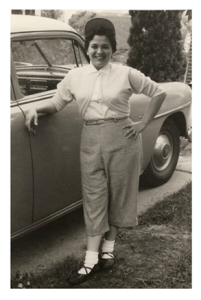

I have written of my mother directly and obliquely, from a place of remove and likewise, from deep inside a mix of emotions. The woman who bore me was formidable: She remains the shadow that accompanies me in my writing as she does in nearly every aspect of my life, the specter that is most frightening in my nightmares and poignant in my daydreams, the cautionary tale of what may happen when we push away those we love, as she did, with verbal jabs and disrespectful acts.

At times, our convoluted history has been instructive. My approach to my children drew lessons from her parenting; I did the opposite of what I thought she might. Often, I have adjusted my own behaviors when elements of her emerge in the content of my responses, or I hear her patronizing tone in my voice. Yet I have adopted her priorities when it comes to the importance of learning and the arts. And I am grateful.

I often think of my mother at Thanksgiving, one of her favorite holidays full of exuberant cooking and invited guests. I certainly think of her during the month of December, as I recall the way she decorated the mantel with relatively little – a bit of greenery, a few objects she enjoyed, paperwhites pushing upward into full bloom from their terracotta containers. Only now do I realize that I decorate in a similar fashion, though I have a Christmas tree in my home, which was not allowed when I was growing up.

I think of my mother when I look at my sons; I recall her playing with them as babies, and I smile.

I also recall when she lashed out at one of my little boys with the same cruelty she previously reserved only for me. I was livid, and after consoling him, consoled myself that his time with her was limited. I have never understood the origins of that cruelty, and why she was unable to find her mirrors, to see herself clearly and perhaps, to dismantle the barriers between herself and those who loved her.

I also see my mother when I gaze into my own mirror; I see her when I gain a few pounds and even more so, as I grow older. The view is disturbing: “I will not become my mother” is the mantra I’ve lived with all my life, and I thought I would be freed of her in some measure when she passed away. Yet she remains my ambiguous apparition, the naysayer in my head, and equally, the fine spirit to whom I owe my greatest passions.

Ongoing Conflict: Mothers and Daughters

While there were periods of my life when I felt my mother’s pride, there were more when I felt unloved, which is not to say that she didn’t love me. Still, I could not understand what I had done that she couldn’t express her love for me in a way that wasn’t spiteful or even diminishing, why she wouldn’t allow me to “own” myself – not my achievements nor my emotions, not my friendships nor my physical space.

She inserted herself into conversations with my friends, she took confidences I shared and spun them into tales to amuse her audience, and as locks were not allowed in our house, she would barge into my room unannounced any time she pleased. This is less of an issue for a child with an open door, and a serious infraction to the adolescent attempting any sort of independence or boundaries. These are minor examples; they nonetheless took a toll.

Through all this, which I had no way to understand or articulate, my friends found my mother to be entertaining and interesting. (Perhaps I prefer the shadows as she always took the center stage.) She was able to draw strangers to her with extraordinary ease; she was known to exhibit acts of incredible generosity; her curious mind and adventurous spirit remained intact well into her 70s.

The calmest period of our relationship was during my marriage, as she adored my husband. By marrying and then having children, somehow, I had finally won her approval. When divorce exploded onto the scene and my mother sided with my estranged spouse, actively supported him in our legal and emotional battles, and welcomed him into her home to live for an extended period of time as a “loving son,” I was bewildered and of course, felt betrayed.

There were other betrayals. I have tried to bury them.

My mother passed away before we resolved our differences, though we were both attempting to rebuild some sort of bridge.

Unloving Mothers, Daughters Feel the Taboo

Clearly, I’m not alone when it comes to feeling as though I was inadequately loved by my mother. Just as clearly, I’ve been able to be a loving mother to my own children in spite of it.

There are many theories on unloving mothers. Some of us simply aren’t cut out for all that’s demanded. Some of us carry deep-seated wounds into our adult relationships, during the years we’re raising children and on into their adulthood.

Psychology Today offers a variety of reasons for the unloving mother, and explains:

The taboos about “dissing” our mothers and the myths of motherhood which portray all mothers as loving isolate unloved daughters, and that discovery lifts part of the hurt and the burden but not at all of it.

I have told myself for years that I resemble my father, not my mother. Point of fact: I resemble them both. Yet when I hear a comment that I look like my mother, I am disheartened. I struggle to see her beauty through the veil of hurt, and thus I am unable to find the beauty in myself.

Whatever the relationship, through parental absence, presence, acts of commission and acts of omission, the mother-daughter bond is fundamental. If we’re lucky, the relationship is primarily supportive and loving. Or, as we mature as women and mothers ourselves, we can look kindly and reflect, finding the moments we will cherish, and forgiving what we must.

Part 1 in a series on mother-daughter relationships.

You May Also Enjoy

I have written about my relationship with my Mom many times in my blog. Daughters and mothers are an interesting dynamic. I wished for and only wanted boys and that is what I was blessed with. So much easier to deal with them and to deal with my Mom as I could always say, “you raised girls so you don;t know boys.” Worked for me. Great article and series.

I know what you mean about boys, Madge. I’ve watched my friends with daughters struggle far more than I did, having sons. Of course, I have also seen both mother-daughter and sister relationships that are so wonderfully close and supportive that I find myself imagining what that must be like. I think those mothers are amazing, to be able to forge those bonds with daughters.

I have a good relationship with my mum, but also have always wondered what it would be like to be a mother of girls (I am the eldest of four) instead of my being a mum of three boys. Curiously my mother has always (with or without reason) been extremely critical of mothers of boys. As in they are probably spoiled, and no girl they bring home will ever be good enough. Where she got that idea, I don’t know. In my circle there is one mum whose relationship with her daughter has been tense pretty much from day one. They seem to be competing whenever they are in the same room some 30 years later.. Yet her relation with her son is based on solid trust and comfort. You have given me much to think about.

I know this piece was difficult for you to write. But, it’s wonderfully written as a balanced view of your relationship. The mother-daughter dynamic is a strange one in many ways. It’s more love/hate than the one between daughter and father. I have been very critical of my mother over the years and have only recently been privy to some of the underlying circumstances that probably contributed towards her behaviors. I’m more tolerant of her now….and the fact that she’s nearing 80 and may not have that many more years on this earth. This reminds me that my time with her is more precious than I realize.

Thank you, Lisa. One of the benefits of growing older is that broadened view of circumstances you speak of. And time is indeed precious. I wish you a great deal of it to enjoy with your mom.

The mother-daughter relationship is so complicated — what you’ve written is clearly tempered by a lot of reflection. I look forward to reading more. Your voice on this subject has always been one I’ve found grounding when I’m working through my own struggles with being a daughter to a mother caught in a difficult marriage. I know our circumstances aren’t parallel, but the larger lessons in negotiating an understanding of who we are because of our families have always resonated with me.

Thank you for reading and commenting, CT. Those lessons we come to understand – especially when it comes to identity – are so critical. I continue to read your marvelous essays on family dynamics at your site, and look forward to more.

Thank you for this.

The mother/daughter relationship CAN be complicated, and I have written about mine with my mother before (she charismatic, critical and not capable of unconditional love and me shy, isolated and in desperate need of nurturing that I did not receive).

She did give me a precious gift – how NOT to mother, and either I learned this lesson well, or have been incredibly lucky, but my daughter, now 19 is my best friend, and I hers. We are so close, and part of this closeness is because she knows I am always there for her. And love her to bits, unconditionally. I have gone out of my way to be respectful of her confidences, to listen before I speak, to apologize when I have been wrong/irritated/impatient/caused her embarrassment (singing or dancing in public, wearing my mustard coat to pick her up at school or when stupid things fly out of my mouth etc.) I have seen my role as life coach. My mother saw hers as a dictator who could never be questioned, could never be wrong.

I share common experiences both then and now. My mother’s cruelty came in the form of passive-aggressive belittling..still happening and challenging for me as I am to be her caregiver. One of the best things that happened as a result of this deeply flawed relationship is that it made me a better mother. I learned the importance of showing love, of being supportive and of creating accepting, open communication with both of my sons.

My mother wonders why she isn’t close to any of her grandchildren and she seems to feel that loss but lacks the awareness, I think, of how her behavior contributed to the gulf. Thank you for sharing your story–it helps so many of us who have and are still struggling with mothers!

That awareness is so important, Walker. I’m sorry your mother doesn’t have it. Nor did mine. And I admire your strength in nonetheless caring for your mom as she grows older.

This resonates so deeply with me, this mother-daughter bond. I had a good relationship with my mother when I was little but I witnessed too much suffering on her part, and all of it was, as she always said, was for my sake. She stayed in a terrible marriage for me, she sacrificed her savings for my college education, she did everything for me. Lucky me, right? Except now, that has become such a burden. And to have seen her make decision after decision that was seemingly right for me but so wrong for her, I vowed that I would parent differently because I couldn’t bear to burden my daughters with the guilt that I bear now.

She became embittered by her choices and she also took my ex’s side when I divorced him; the older I got, the more distant we became, magnified by the physical distance between us.

These days, conversations with my mother are pleasant but we don’t have much in common. She is proud of me and loves my family and me, but knowing that I could never be her, nor do I want to be, has helped me make better decisions for myself and my girls. But I don’t always win – sometimes I hear my mom’s words coming out of my mouth when I’m with my girls, and it scares me. I want desperately to have something different with my girls. I wish to inspire them with my actions, not my words, but the shadows from my childhood loom large and dark above me.

My mother was unfailingly loving, cheerful, industrious, gregarious and humble. She loved to play the piano and the organ and, during her last four years, to spend time with her one little grandchild who lived nearby. She had a big house to keep, and although I don’t think she relished doing that very much, she never complained about anything. After her children had left home, and particularly after the family dog and cat had died, she became very lonely for my father, who was married to the practice of medicine. Not one to wallow, she learned to golf and made a new world for herself in the outdoors, and with fellow sportswomen, that she loved. Just as I had grown up enough to want to get to know her better as a person, rather than just as my mother, and she had started to reveal herself to me, she fell ill with what we were told, right from the beginning, was an aggressive terminal illness. During the ensuing five months that she was in a hospital before she died, I spent at least five hours at her bedside (often with my newborn son in a basket under her sink) almost every day. I was desperate to really get to know my mother, and I spent a lot of time when I should have been sleeping trying to figure out ways to get her to talk with me about herself. Unfortunately, pain and acceptance of death had already taken her down the road, and I could not reach her. I realize now that it was selfish and probably was terribly intrusive to try, but try I did, in every way I could think of, to find this person whom I loved so much, but she was beyond me. She came back once, for a few moments, as she held my newborn son the one time she was able, but that cost her dearly by making her want to live. The deep yearning for her that I developed as she was dying has abided within me since, along with the knowledge that I was very well nurtured by her when I was a child. May her soul be at peace.

Leslie, Your comment offers us all much food for thought. Some of us are easier to get to know, as individuals. That’s true for our confidantes, as well as our partners and our children. Others are more reserved in what they share, or allow us in only up to a certain point. Some of these boundaries seem fitting (to me), especially in certain relationships (parent-child). Others may be more restrictive than we would like, especially as adults who wish to better understand our parents. What we cannot necessarily know – how much is nature, habit, or self-protection for reasons we may never be aware of.

There are practical aspects to knowing our parents more intimately as well. I realize that had my own mother and I been communicating more consistently (and better), there were aspects of her health that I ought to have known, frankly, that are useful to myself and my children. As much can be passed through genetics, a little knowledge can go a long way – and in some instances (in my own life), already has. Still, I wish I had known and understood more. Not only for the pragmatic, but the emotional clarity.

That your mother had that lovely moment with your newborn seems like such a gift. I’m happy for you that she had it, and that you were able to be there to see it.