It’s a statement that appears self-evident: People who experience a problem are uniquely equipped to solve it.

This sentiment was expressed in a New York Times article, in a very specific scientific context as The Times piece referenced one of the challenges in extracting blood painlessly, and believe it or not, considering the tampon of the future as a vehicle for sample collection.

This sentiment was expressed in a New York Times article, in a very specific scientific context as The Times piece referenced one of the challenges in extracting blood painlessly, and believe it or not, considering the tampon of the future as a vehicle for sample collection.

Now, now. Stay with me on this. It’s a clever idea, don’t you think?

And there are lessons to be learned.

The Truth, the Whole Truth, and…

All smirking at the subject matter of The Times article aside, here are two points that arose out of subsequent conversation with a friend, and my own musings that followed.

First, there is my own “truth” that living a problem provides unique insights into resolving it. So, in principle, I fully believe the statement that I opened with.

Second, I am aware that “truth” is not universal and not objective, each truth unfolds within other “truths” (or givens), and the greater the distance from a provable fact, the less we can rely on that truth as anything more than hearsay (at worst) or ideology (at best).

Mind you, I do indeed believe in verifiable facts. However, I understand truth as perceptual and interpretive, subject to the mind’s foibles, faults and follies much like philosophy or any belief system, and some might say, accepted “knowledge.”

As for the concept of “the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth?”

Ah… those words whisk me back to memories of childhood, to sneaking out of my bedroom into the darkened hallway, and to flattening myself against the cool hardwood floor outside my parents’ room — all so I could peek through a crack in their door to catch an episode of Perry Mason on the RCA.

In other words, there are few absolutes (though some of you would disagree), “the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth” included, and likewise the accuracy of my Perry Mason recollection, not to mention the role of personal experience in problem-solving. And on that, my point of departure, I do indeed view “living with a problem” as helpful to finding a solution, or a broader set of options, or a more compassionate approach to what it takes to even offer some hope.

I believe this to be the case especially when experience is coupled with a natural inclination toward self-interest (not a dirty word, by the way), and in combination, they give rise to significant and creative discoveries.

Would you like an example? Here’s an easy one. If you’re living with a medical condition that physicians dismiss — they blame it on your mood, your stress; they serve up platitudes and Prozac — aren’t you likely to seek answers on your own? Isn’t the reality of your experience motivation to persist? Aren’t you able to feel empathy for others in similar circumstances?

Problem-Solving: Necessity Sparks Invention

I am reminded of this adage I learned as a child: “Necessity is the mother of invention.” That’s all well and good, and as we observe an adult or child in an exploratory state of want or need, we might see a variety of problems solved.

I have an example of this to offer as well, albeit extremely simple. As a petite woman, it is routine for me to enlist the help of strangers to reach things from shelves or racks when I’m out shopping. You name it — the hardware store, the grocery store, or for that matter the overhead bin in a 747 — the “problem” is reach and access; the solutions involve objects to poke, hook, or nudge a box or can, to knock it down into my waiting hands, or… scanning for an available candidate to help. That candidate, male or female, must be near enough (and tall enough) to come to my aid.

This “skill” at managing in a world that is slightly too tall for me is my “normal.” The result? Whether creating a makeshift rod or step stool, or reading the faces of strangers, my “necessity” has demanded creative solutions — all manner of ways to get what I’m after when there is no one around to assist.

What would really come in handy?

Off the top of my head, a small object with these characteristics:

- Folding / unfolding much like an old wooden carpenter’s measure

- Sufficiently collapsible and lightweight so that I could carry it in my purse

- Extendable up to about two feet, to nudge or nab an object

- Outfitted at the tip with some sort of prong or pincers so one could actually pick up a box rather than toppling it and hoping for a good catch

Hello? Does this exist? Quite possibly. Have I simply not searched on GadgetsForLittleWomenRUs.com?

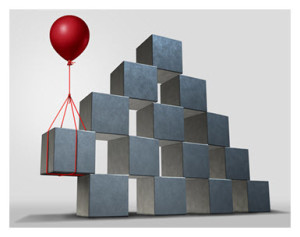

When faced with a gnarlier dilemma — rarely is problem-solving as straightforward as what I’ve just described — cue the call (or scream) for out-of-the-box thinking. Or, if you prefer, a cutie-Patootie MacGuyver to the rescue, as he thrills without need of steed, ditto on the knightly accoutrements, outfitted instead with brains and a paper clip.

Ah, Genetics, and the “Born” Problem-Solver

This March 2015 article in The Guardian UK asks if genes determine our entire lives, and at the mere mention of the title, I feel myself raising an eyebrow and considering problem-solving.

Are personality traits inherited? Are talents inherited? Don’t we believe that environment is crucial to developing or hampering the innate positive traits we are born with?

Is there any reason to think that problem-solving skills — be they mechanical, mathematical, or interpersonal — are more or less likely to run in families? Haven’t we all observed precisely this? Do we accept that we are all dealing with a deck that may be genetically stacked, all the while that same deck is environmentally influenced by people, circumstances, random events, knowledge, skill, and a bit of luck?

Clearly, I am not a scientist. And while I might once have considered problem-solving to purely consist of learnable skills — I’m using a very generalized notion of problem-solving, I realize — 20+ years of parenting has led me to believe otherwise. And this isn’t only in observing my children, but in observing the many others whom I have watched grow up alongside my own.

Take my firstborn son as an example. He possesses an uncanny ability to look at a broken object, tinker with it, and magically (to me) — fix it. His analytical mind is also naturally tuned to size up complex conceptual issues, and he is able to communicate them in comprehensible ways to others. Frosting on the cake?

Happily, the array of problem-solving flavors that seem second-nature to him is extensive, each layering and reinforcing existing skills, while prompting the emergence of new ones.

Interpersonal problem-solving?

Interpersonal problem-solving?

That’s another matter. Mature though he has always been, I would hazard a guess that he, like the rest of us, will need to live his share of emotional wins and losses before grasping the nuance and variation in human connections.

Still, he has always been, to a remarkable extent, what most would term a “born problem-solver.”

Anecdotal?

Absolutely.

But also, my “truth.”

Psychology Tells Us…

Some of us appear to be better at problem-solving, but maybe our talent is for superior or speedier problem definition. And identifying the problem — the right problem — is key to resolving it.

Returning to the opening premise — that those of us who live a problem are more equipped to solve it — isn’t it the fact that we have a vested interest, that we live with the details, that we possess an intimate knowledge of our less than desirable state, that we see the ripple effects on those we love, that we’re in want or need or pain and these last elements especially compel us to describe all the angles and impacts more clearly, and that in turn, increases the likelihood of a hastened and more complete solution?

(Yes, I know. There are assumptions and issues with both those terms — hastened and complete.)

This Psychology Today post on How to Solve Problems Like an Expert explains:

… inexperienced problem-solvers tend to jump right to the solution stage of problem solving, with typically disastrous consequences. They often use a trial-and-error strategy… In contrast, experts tend to spend more time developing a full understanding of the problem…

“A full understanding of the problem.” Yes. There’s value in precisely that.

This same article notes that “ill-defined problems… don’t have clear goal states” — in other words, explicit, measurable outcomes. And, comprehending the problem is vital to organizing the knowledge needed to generate potential solutions.

Then again, we all possess different temperaments, different capacities for comprehension of various subjects, and different innate skills like the mechanical magic that comes so naturally to my elder son.

My mechanical abilities?

Well, you could say I’m trainable. With repetition, that is. A great deal of repetition. On the other hand, I possess other innate capabilities, and a broad base of judgment enabling me to use them well, and compensate for those I do not have.

Questions, Questions, Questions… and Teamwork

What else enhances problem-solving, whether you live with a problem or not?

Try these: Asking the right questions, soliciting assistance, staying open to new ideas, thinking outside the box, and recognizing that we may live a problem and not have the knowledge, skills or other competencies to solve it.

The first two — asking questions and asking for help — are essential. We cannot shut doors with assumptions, isolation, or ill-advised convictions that “our way” is the only way to an answer. Two heads are often better than one; at the very least, we can avail ourselves of others with whom to float an idea.

Incidentally, I do not wish to neglect or negate the contributions of those who will generate ideas and provide solutions without personal experience as their guide or incentive. Unfettered by history, or simply wildly imaginative, those with a “why not” approach to problem-solving can be very useful. Nevertheless, depending upon the nature of the issues being addressed, if not actual “skin in the game,” a sense of it surely reinforces commitment to resolving the challenges on hand.

So, in considering my stumped and stymied state when confronted by mechanisms I cannot fathom (as my son typically shakes his head), you have an example, however benign, of living with specific needs but not possessing what it takes to solve them — not the big picture, not the details involved, not the dependencies, not necessarily the repercussions.

And that leads us to these equally self-evident statements that I will only mention briefly. First, we may do well to enlist an assist from a qualified party, and at times, a disinterested one at that, who is not “living” the problem. This gets the job done with no sticky emotional entanglements, and possibly a dose of objectivity we need. Second, all problems are not created equal. Clearly, solving a medical puzzle is higher priority than yours truly reaching a can of black beans on the top shelf at Trader Joe’s.

Skin in the Game; My Skin in My Game

All hail the friend or family member who listens, who offers suggestions when asked, and who readily states “this isn’t something I know much about,” when he or she isn’t qualified to judge or advise.

And let’s give it up for the intimates who are forthright enough to admit their bias and their agendas, though in my lifetime thus far, this sort of integrity has been rare.

All the more reason that it’s important to understand when skin in the game serves us, and when it skews recommendations.

All the more reason that it’s important to understand when skin in the game serves us, and when it skews recommendations.

All the more reason that it’s important to prioritize, whether dealing with personal, organizational, or societal problems, though disentangling complexity makes this easier said than done.

All the more reason that we should encourage participation in problem-solving so we may encourage a diversity of angles and approaches, though this too is easier said than done, and is more effective with relevant skill sets and experience. (There’s that word again — experience.)

All the more reason that innovation — or just a damn good decision — may arise out of discomfort, frustration, inconvenience, or simply persistent need. Living with persistent need. From need and the “truth” of experience, with a little luck, we just may find our viable solutions.

Is this too much abstraction for some of you? I’m guessing that’s a yes.

Try this for a dollop of specificity: I find myself starting over in midlife yet one more time, in significant ways, and all simultaneously. Work life. Personal life. Possibly, relocation. Consequently — to stave off a minor nervous breakdown? — first, I remind myself to breathe. And then, I tell myself to distinguish soft limits from hard constraints; to examine presumed truths and allow for their alteration or dismissal; to seek the wisdom of my previous experience and use it to my advantage; to pay attention to the lessons I’m picking up along the way; and to share those lessons if I can.

Having gone through these changes before, the process is less frightening than the first time. And, I know the pleasure of the serendipitous discovery, the power of my own attitude and actions in creating my future, along with well-worn “problem-solving” skills to help me along the way. On the other hand, I’m a dozen years older, with fewer financial reserves, less room for error, and aging as a single woman in the U.S. does tend to place more challenges in our paths. Agree or disagree with that final observation, but that too is another one of my “truths.”

You May Also Enjoy

Wow…well, the easiest thing to comment on first is the problem solving dilemmas. Being on the shorter side, myself, I have found that I always have to ask for assistance when trying to reach for things that are too high, or lift things that are too heavy. I have to ask, even if someone taller or stronger is seeing me struggle. You can imagine how “blown away” I was in France when my luggage was lifted and placed where I wanted it, without having to ask for help. All men…of all ages, automatically helped me…even as I was carrying things, myself. This attitude and courtesy was everywhere in France…from Paris to Provence. Yet, when I boarded the plane to return to the U.S., a young man (American) well over six feet tall, and an elbow length away, watched as I struggled to place my carry-on in an overhead space. I refused to ask him for help, and he certainly never offered. So, it was definitely back to reality.

I tend to believe problem solving skills are innate. And, for those born with those qualities, I think having problems to solve really hones those skills. I believe the ability to remain calm and focus on one’s current dilemma, aids in being able to find a solution. When I see people crumble in the midst of turmoil, it is usually because they have panicked and lost focus of any possible solution. Truth, awareness of others and oneself, is essential to correcting any “wrong”…and believing in your ability to overcome, or make things a bit better is key. Whatever constraint/s I may be facing, I try not to be victimized by them. Just the other day, I was so impressed with a very young waitress, I asked questions about her current work/study situation. She told me she just finished her first year of college, but wasn’t sure she would be able to continue (and here she listed a host of problems). I told her to think about each problem, separately, at first, and try to come up with a way to solve it. I ended our communication by telling her that it is always easier to give up when you’re faced with obstacles, but she owed it to herself to pursue her dream because she was, in fact, designing her life. Afterward, I reflected on my advice to her and thought how wonderful it would be if I could always follow my own advice!!! Happy 4th…may we all be independent thinkers and doers!

I’m nodding at your comments, Angela, for so many reasons! (Not the least of which is the chivalry encountered in France, nor my own befuddlement on a plane not so long ago when a flight attendant who had to be a foot taller than myself watched me struggle with a bag, so I asked a passenger to help!)