Becoming. It’s the word my mother frequently substituted for “attractive” or “pretty.” “That’s not becoming behavior,” she would say. Or: “That dress is not becoming on you.”

Criticism came easily to my mother.

Criticism came easily to my mother.

The words we hear early in life, especially when they are repeated, make their way into our consciousness, our language, our inner dialog.

I heard “not becoming” far more often that its positive alternative. As I consider this realization, sifting through the deeper meaning behind those words spoken by an exceptionally articulate woman, it’s as if “not becoming” was a carefully positioned obstacle, an interdiction, a refusal to sanction the forward movement that we all seek, the process of becoming who we are.

When we cannot become who we are, sometimes we become someone else. We engage in the insolent and necessary act of poking through the darkness, scratching at walls, then slithering out of the cocoon and transforming into something, anything… someone, anyone… just to make our escape.

We cannot all emerge from our cocoons alive and whole, much less as butterflies. Some of us are bound to be moths.

Though they may not hold court like the monarch, even moths are lovely when you pause a moment to follow their flight. They know the advantages of traveling under the radar. They drift on the air and explore the sky. They know the light and chase it.

Perhaps to be a moth is a gift.

Echoes

Stunted, stalled, stopped. These are words that come to mind. These are words that describe and circumscribe, that contain and constrain, that arise out of memories of the woman I adored in some respects, feared in others, and loathed at moments.

My mother was a formidable figure. She awed those in her sphere with her brilliance, her quick wit, her indomitable imagination. She enchanted admirers with her perfectly symmetrical and exquisite face. She was also a force to be reckoned with.

My mother intimidated those who threatened her, questioned her, or those she disliked; she made me feel small, swallowed up, silenced. She had a habit of raging at the world in my presence, and I would slink away if I could. Only years later did I permit myself to rage in turn at her, always in isolation. As a child and adolescent, I swam in insignificance, hiding my most vulnerable self away, consoling myself any way I could from hurts that seemed to stack up day after day.

Writing and drawing allowed me a measure of safety and a whisper of a voice, though I look back and see that as long as I lived in her shadow, I was “not becoming.”

In her bigness — not to be confused with largesse — the obesity that eventually took her life made her seem invincible. She was loud, she was demanding, she didn’t listen. Oddly, she died quietly, without fanfare or warning. She was found one morning in her rocking chair in front of the television, seventy-something, chin down, body upright.

It was an incongruous end.

Do Dreams Signal Revelation or Change?

I blame the dream on my mother’s recent birthday.

I blame the dream on the Hepburn classic, Funny Face.

I blame the dream on Caitlyn Jenner, so much in the news.

There is no blame in dreams of course, only discovery, revelation even. And possibly, motivation for change.

That the calendar would signal awareness is hardly a surprise; I still recall my parents’ anniversary as well as their birth dates, along with those of my grandparents. Not long ago, wishing my mother a happy 80-something in my mind, I had gone about my daily business as usual.

As for Hepburn, her character in Funny Face is plucked from a Greenwich Village bookstore and thrust into the role of fashion model. She has a part to play, though it isn’t “who she is,” and she tows the line in order to get what she wants.

In the dream, Audrey makes an appearance in pony tail and capri pants, then briefly in a satin gown on a 1950s Paris runway. Caitlyn Jenner, in the media everywhere we glance, seems to hover on the edges of the scene. My mother, though I cannot find her, is somewhere on the premises.

I am the protagonist in my sleeping mind’s strange clip, a place of prominence which is, for me, an exception. I find myself in a large room, getting out of a single bed, and as I stand up, I’m aware that I’m a fifty-something year old man. Or rather, I am me — female, tiny, fifty-something — housed inside a broad-shouldered, physically strong, six-foot tall male body.

As I look around, I notice that the room is a gallery. I am the featured artist, and my paintings are on display. Women are approaching me and lauding my work, and as “myself” inside this masculine guise, I am fascinated: All I need to do is nod and smile and offer mindless small talk, and the accolades are rolling in. I am also appalled. My thoughts are the same as always. My conversational style is the same as always. The artist who painted these images is the same — me. The response to a man — one with a commanding physique — is entirely different than anything I’ve ever experienced as a woman.

From here the details blur: I’m trying to concentrate on what is being said, but it is difficult and tiring. I’m monitoring two selves — the inside self, the outside self. When a woman makes a blatant pass — she adores my work (she says), and won’t I come over one evening — my inner female is amused. I wonder if I would ever be so brazen. And then I drift into waking as “the real me,” and it is both a relief and a disappointment.

I am small again.

Of Cocoons and Chameleons

I know what it is to be a chameleon — to change languages and cultures, and try to fit in. Sometimes you do, sometimes you don’t. Sometimes you wish to be invisible and to flit like the moth from light to light.

I know what it is to be a chameleon — to change languages and cultures, and try to fit in. Sometimes you do, sometimes you don’t. Sometimes you wish to be invisible and to flit like the moth from light to light.

Sometimes the light is brighter in this new place. Sometimes the light is clearer in this new you. Sometimes, you become the light for others.

I know what it is to be a fat woman, though my years in that state were fewer than my mother’s. Yet I understand what it is to become the object of cruel jokes, to be among the dismissed, to find yourself perpetually overlooked.

I know what it is to compensate when the outside has little to do with the inside. You blossom any way you can. My mother was an excellent role model in this; her intellect flourished as other opportunities withered.

If we imagine ourselves emerging from the chrysalis, and during our lifetimes we manage survival as chameleons when we must, these metaphors take us only so far. We have more than a single shot or the housing of our birth: We are capable of retreating and spinning a new cocoon, which enables us a multitude of refashioning options. Still, we can neither fit in nor fly absolutely anywhere we please. We cannot shake certain aspects of our grounding.

That my dream is about transformation is obvious — Audrey Hepburn’s fictional character from bookish sales girl to intelligent beauty; Caitlyn Jenner from middle-aged man to middle-aged woman; my mother from lovely youth to angry, unhappy adult. Equally evident is the worry that I will become my mother — shut off from acceptance, understanding, love. In the examples paraded in my dream, I see varying degrees of living life by mask, and in my mother’s case, a conundrum as to the many selves she was, and the monarch she might have been.

As for my time inhabiting a man’s body — stronger, more powerful, less fearful of the future — I assess the lives I’ve led, the roles I’ve played, and I wonder if I would have done more, been more, and contributed more as a man.

Dreams Unearth Our Stories

My mother was the queen of the backhanded compliment, if there was a compliment to be had at all. Surely she received many herself, so why she couldn’t dispense them is a mystery.

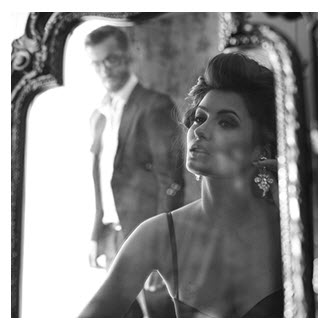

I recall her dressing for dinner out, pearls around her neck, red or coral lipstick in hand, gazing into the glass above her bedroom bureau. She was making sure she was “just right.” My dad was hovering somewhere in the background. These are immutable images; frames extracted from a child’s memories.

I am told that even as a teenager and a young adult there were issues, though she appears pretty and sweet in the few photographs I have of her from those years. I know none of the details and can only hazard guesses. She was a child of the depression and a teen during World War II. My grandmother, whom I loved deeply, was raising children alone while my grandfather was stationed in the Pacific. My mother was frequently tasked with caring for two younger brothers who, incidentally, also passed away as the result of complications caused by obesity.

By the time I was 11 or 12, all I could think of was the day I could get away from her. I didn’t know why I was the target of her anger, why she had me bear witness to her bouts of bingeing and sobbing, or why she could never seem to fill herself up.

As an adult, I have asked myself how she became “that” woman. I have theories of course, but answers are impossible.

It is rare that my mother appears in my dreams, so when she does, her presence stands out. The sense of her proximity is unsettling, especially as I grow older, though the yearning for our relationship to have been something else, for her to have been something else, for her to have become a different version of who she was leaves me, for a time, bereft.

I catch my breath in a realization: While my mother was impatient and abrasive with women, she couldn’t have been sweeter when dealing with men. Even in her seventies, she catered to them, complimented them, nurtured them, flattered them. How does this play into my masquerade as a hardy, attractive middle-aged man?

Becoming… in the Mirror

Who did my mother see all those years when she looked in the mirror? Who did she see in the background when my father was an active admirer in her life? How did she process the changes when he was increasingly gone, and she buried her heart beneath one hundred pounds of excess flesh?

Even when she was cruel to me as a child, as soon as she flipped that switch to “off,” I saw warmth in her smile, sparkle in her eyes. With the years, those glimmers grew fewer.

Even when she was cruel to me as a child, as soon as she flipped that switch to “off,” I saw warmth in her smile, sparkle in her eyes. With the years, those glimmers grew fewer.

When my mother looked in the mirror, was she “becoming?” Who and what was she becoming? Did she see herself as she was ten or twenty or even fifty years earlier, the lithe adolescent planning a perfect future? Did she see the curvy but stunning twenty-something, in love with a “nice boy” and his clean Clark Kent look?

As she grew older, my mother had trouble with mirrors.

As I grow older, I have trouble with mirrors.

If my mother distorted her reflection to survive, I understand. If she avoided reflection of any sort to survive, I understand. If she could not find her own trim and elegant mother in the image that gazed back, I understand. On the mornings and afternoons and evenings that I glance into the mirror as the years pass and it is my mother’s face that looks back at me, I understand.

Like my mother before me, I long to see her mother gazing back.

In front of the mirror on a shadowy day, I move past “not becoming.” The progression is both natural and all wrong; what appears to the onlooker has little to do with what beats inside. I observe that I am “unbecoming.” Perhaps in middle age we are all unbecoming.

Images Leave Clues

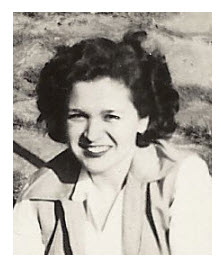

After the dream, I went searching through files to find photographs of my mother. Tucked between legal papers were pictures from the 1940s and 1950s, most of which I don’t recall seeing. In one, my mother is a teenager, 16 or 17, with a tiny figure and a big hat. She strikes me as very “Vita” — Ann Blyth in the film, Mildred Pierce. My mother seems so proper, so pretty. But what is going on inside?

Another photograph shows my mother in her early twenties. She is fuller figured as was the norm in the 1950s, and from the hair and setting, I would say the picture was snapped around the time she married and certainly before children. The smile on her face is open and sunny. She’s lounging on a beach chair on Atlantic City’s Boardwalk. A man’s shoes sit on the ground beside her. I assume they belong to my father.

Another photograph shows my mother in her early twenties. She is fuller figured as was the norm in the 1950s, and from the hair and setting, I would say the picture was snapped around the time she married and certainly before children. The smile on her face is open and sunny. She’s lounging on a beach chair on Atlantic City’s Boardwalk. A man’s shoes sit on the ground beside her. I assume they belong to my father.

Trying to connect the dots of my dream, my attention to these images, and the very fact that I have no recollection of them and they seem so telling — how do I reconcile all the ways in which any of us are “becoming,” only to find ourselves stunted, stalled and stopped?

Then I remind myself: There were corridors blocked by her self-destructive habits, by the walls erected of so much fat, by her refusal to listen to reason about her behavior or her physical health. Yet none of this prevented my mother from developing her mind or making a mark on the people around her. She attended college in her thirties, while raising children. This was in the 1960s, when few women did so. She hiked up mountains — literally — when she was in her early fifties. She returned to school to study Japanese in her sixties and seventies.

These accomplishments are impressive, to say the least. If she found aspects of her life to be denied her, stowed behind impenetrable doors, there is no question that my mother redirected her efforts to create and exploit other opportunities.

Our Parents, Ourselves

So what of my dime store psychology? My dream analysis? My desire to flood my mind’s rooms with light and throw open the doors I perceive as closing?

We all wish for our parents to love us and protect us, to honor us as we are. We wish to be mothers and fathers who encourage our children to feel loved and accepted as they are. We hope our children will pursue a life they feel good about, and find a person to love who will love them back — as who they are.

That I think of my mother at certain times is inevitable. That increasingly, I look into the mirror each morning and see her, then turn away, may also be inevitable. I recognize my options to continue gazing, to see her differently, to see myself differently, to separate the two of us more clearly if I can.

The closest I’ve ever felt to living in the wrong body is during the years of my considerable overweight, years during which I could also have been termed obese — carrying some 50-odd extra pounds on my five foot frame, which was nothing compared to my mother’s equally small stature struggling at 250. What I recall vividly of these years is the impression of misalignment between my outer and inner selves.

A sense of impotence tagged along for the ride.

I am familiar with impotence in other ways as well — impotence as a provider comes to mind — wretched periods of underemployment and unemployment. My sense of powerlessness was profound, and my self-esteem, shattered. In this, some say, I more resemble a man.

I am familiar with impotence in other ways as well — impotence as a provider comes to mind — wretched periods of underemployment and unemployment. My sense of powerlessness was profound, and my self-esteem, shattered. In this, some say, I more resemble a man.

Perhaps this is because, like my mother, I turned away from more traditional female opportunities. I invested myself in other avenues where I could excel.

Who We Are, Who We Are Becoming

Would that we could all select the elements of personhood that make sense, that feel natural, that are useful; that we could inhabit our many aptitudes and dreams without superficial barriers; that we could be accepted as we are, and accepted as becoming.

Hepburn is a marvel. She will always be a butterfly.

Caitlyn Jenner?

I say bravo to anyone with courage.

My mother’s gifts to me?

They are many, and intact.

While the echoes and shadows have lessened, they have not lost their power.

As for life as a man, I cannot say that I desire it.

I remain admiring of the moth — her persistence, her freedom, the delicate way she flutters her wings. She seems so commonplace that we pay her no mind. I like that, too.

It is not that I want to become someone else so much as I have always wanted to become exactly who I am, even as I discover who that is: writer, mother, lover, listener, dreamer, doer, fighter, friend, maker, and I hope — a woman who will know the light and choose to chase it.

You May Also Enjoy

And a woman who will know the light and bask in it. A woman who will know the light and share it. What a rich piece this is. Dreams are so fascinating to me. I keep a dream journal and recently read that there are dream clubs or groups – like a book club only they come together to analyze, share and make sense of them.

Keeping a dream journal is a great idea, Barbara. I agree — dreams are fascinating! And thank you for the good words.

This is an extraordinary post, extraordinarily honest and at times quite painful to read. As a mother I cringe, and my toes curl as I worry about the ‘harm’ I may have done, for even if we always try our best, the potential pitfalls are large and numerous…

I literally gasped at your phrase “I wonder if I would have done more, been more, and contributed more as a man.” … it has never occurred to me to pose that question, but I think that now I will.

Thank you for such a thought provoking piece.

Sharon

THIS WAS YOUR BEST WORK………………..I was hooked and could not stop reading!

We all have these feelings. Whether we are too thin, too fat, too tall, too short, have a big nose, big ears, or whatever, we are never satisfied with the outside package. It never meets who we are on the inside. This is just part of what being human is all about. Parents are human and as such, they aren’t perfect. Babies don’t come with parenting manuals. What we have to take from all this is look to people who are successful in spite of their shortcomings. Like the surfer girl who had her arm chewed off by a shark. She kept on surfing. Like the soldier who had his legs blown off, he ran a marathon anyway. Queen Latifa, a plus size woman and African-American, could have sat in a corner sulking, saying, “I’m fat and Black so I have disadvantages and can’t shine in life and reach my full potential.” But no, instead, she has the attitude, “I’m fat, so what? I’m Black, so what?” and she ignored what society wanted to place on her and instead, plowed through it all to BECOME a shining star. She never had the “oh poor me” helpless victim attitude. She had a powerful “get out of my way, I’m going to shine” attitude. And that’s what we all need when we start feeling sorry for ourselves and letting pity set in. We need to pick ourselves up and move forward, telling ourselves and the world, “So what, get out of my way, I AM BECOMING!”

I believe most people do the best they can with the cards they have been dealt. A riveting post.

I am new to this site, seems that the posts are referring to a book, not sure what book. But the comments are awesome and meaningful … L