Robert Johnson, King of the Delta Blues Singers they called him, only recorded twice before he was poisoned by a jealous man in a Mississippi juke joint in 1938. There wouldn’t be rock and roll as we know it if there hadn’t been those sessions. First one was San Antonio, 1936. Second was Dallas, 1937. The producers set up temporary studios in hotel rooms or wherever they could and recorded the best sounds they could muster.

Robert Johnson, King of the Delta Blues Singers they called him, only recorded twice before he was poisoned by a jealous man in a Mississippi juke joint in 1938. There wouldn’t be rock and roll as we know it if there hadn’t been those sessions. First one was San Antonio, 1936. Second was Dallas, 1937. The producers set up temporary studios in hotel rooms or wherever they could and recorded the best sounds they could muster.

They say when Johnson played, he didn’t face the crew, he faced the wall. Some say it’s because he traded the devil his soul in exchange for his unmatched talent, and they say he was too evil to face his fellow man. But an engineer will tell you he was probably a damned clever fellow. He probably knew – just knew from the way the room sounded when all was quiet – his guitar would record best bouncing off the corners. Even after all these years, I listen to those recordings and figure it the same.

“Presence” is a technical term for what you hear in a room from where you sit in a room or where you put a microphone. It’s the noise a room makes when nobody and nothing’s making any other noise. When you listen close enough, you hear that a silent room lacks sound the same way tap water lacks taste.

Since I learned the technical term, I’ve been struck by how close “presence” is to “present,” as in past, present, and future. The way I figure it, we want recorded sounds to sound as they would were we present in the room when they were recorded, no matter when we listen. What was and what is and what shall be – always the same.

All of this manifested in my life when I first put needle to vinyl, and when I met some kindly guides from whom I was fortunate enough to learn a thing or two about recorded music. But I was neither a collector’s protégé nor a spinner of hi-fi stereophonics. I was a kid with two simple things going for him: I didn’t know any better, and I was willing to listen.

*

When I was thirteen Grampie showed me how to crank start his 1969 Briggs & Stratton lawnmower. It was seventeen years old then and had more nicks and bruises than I did, dents and rust all over its orange platform, a makeshift choke lever made of a folded tin can. It’s simple, he told me: Keep your feet clear, back and forth across the grass, carve up the lawn into manageable sections, around the trees and the picnic bench and birdbath. He’d stand there watching to make sure I didn’t mess up his mower, or he’d bring the gas can over when it ran dry and watch me pour it around the piping exhaust, because he knew I hadn’t learned to look for that yet.

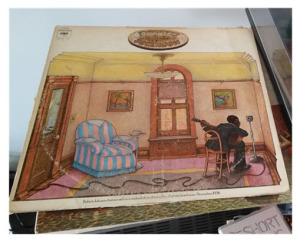

Soon enough, I’d mow a lawn a week and that meant five dollars, and five dollars meant four records at the collectors’ shop in Rocky Hill, a couple miles up the road. Most times I left disappointed. Maybe I’d found a massively popular disc of Creedence or The Kinks for a few bucks, but it was the hidden needles I was after – something undiscovered in the haystack, something whose rarity I’d cherish as much as the music pressed in the vinyl itself.

We would later learn that the record shop was a front for organized crime, the owners, in the guise of collectors, traveling back and forth to and from Chicago to the reputed best of the best of the record conventions. Or were they collectors with sketchy side jobs? Either way, you name it and they’d find it for the most affordable cost to you, the customer. In my case, they knew that price was pretty low; I would open the door carrying a fistful of lawn mowing money, and there were grass clippings stuck to my sneakers except in winter when it was snow on my boots. They knew their business, and I trusted them to help mould my musical tastes.

My mom would drive me and wait in the car while I pushed the limits, seeing how many treasures I could dig out while her patience unraveled. I’d walk in and I’d get so overwhelmed I couldn’t remember a single name I was looking for. So I’d start at the front of the store, which was the front of the alphabet, and work my way back. To this day, most of my collection are records filed somewhere between A to N because Mom’s patience wouldn’t last through ZZ Top, though I’d always make a special run through the S bin just in case, and because Seger was my true quarry. To this day I’ve only got a couple of the most essential Pink Floyd and Rolling Stones, but every Bangles and Grand Funk Railroad you can imagine.

One day I asked the shop owners about a particular Eric Clapton album I’d read a review of at the library across the street. My other obsession was to create a “family tree” of rock and roll through the album credits, which I would pour over and memorize to an eerie level of accuracy. Though they didn’t have the Clapton record in stock, they recommended J. J. Cale’s Troubadour, if I hadn’t heard it – which I hadn’t. I knew Cale had written some of Clapton’s hits, and I knew he’d played on Seger’s cover of the Allman Brothers’ Midnight Rider on his Back in ’72. That was one of those hard ones to find, discontinued since a single run in 1973, but the guys had gotten hold of a radio station promotional copy that set me back five weeks of lawns. It was worth it.

As we exchanged precisely five dollars for Troubadour, the guys at the record shop said to me “Cale will blow you away.” Now I’ll confess I was disappointed with Side one Track one upon first listen, but I respected their words. So I stuck with it, ending with the track Clapton immortalised, “Cocaine.” Cale’s original version is weird – or at least it was to a teenaged boy with a lawnmower ringing in his ears, shifting back and forth from speaker to speaker trying to find just the right spot to feel the music. Trying to be blown away.

But let me tell you, by the second time I played it, Cale’s Troubadour changed the way I listened to music. Side one Track one again: Hey Baby. The credits read “Recorded in a Log Cabin, Murfreesboro, TN.” Now that’s a story you can hear in the performance if you listen closely. If you listen for the presence of a log cabin. That’s what I mean about presence. Maybe you can’t see it, but you can sense it. It’s there and it wants to be known.

I looked up Cocaine at the library (a funny thing to ask at the reference section), and I don’t know whether it’s true, but they say Cale recorded each string on the song to a different track and mixed the chords rather than strum them. Well, that made some sense of the oddly staccato rhythm and this sound in this speaker and that sound in that speaker and the cacophony of unfamiliar noises. After a while I figured out a whole production, a mix, tells stories I’d have missed had I not slowed down to hear them through.

In a log cabin, I thought. One string at a time? If Cale can do this in a little wooden room, surely I can grow up in a little plaster room with a second hand guitar and some second hand hopes. If he’s got this kind of patience… If he can flout the rules like this… couldn’t I make my own way, too?

Smooth sounds of Tulsa-grown country jazz rock, layered delicately, delivering his guitar lines without a wobble and without flash, near-whispering the words so deep in the mix you’d strain to find them. But that straining opened up the space, revealed the room, the Log Cabin. I absorbed Cale’s laid-back sounds, and whether I’ve succeeded in my aspirations to emulate his no-nonsense rebellion doesn’t matter as much as the act itself. Aspiring can be its own end.

To say this music grew on me is to betray my love for it. This recording directed me down a path, issuing guidelines etched into its mere existence. Listen with patience. Listen closely. Listen in the present, in the Log Cabin, with Cale. And my love spread to the medium of vinyl itself, to the experience of holding the records by the edges in my hands, to watching the needle cut through a physical groove to transform shape into unseen sound – drifting, blasting, transporting me to this past, to that day in a log cabin in Murfreesboro, TN, as though we lived and listened in that ever present, promising that as long as I take good care of the discs, I’ll always have these songs and stories.

These albums with their gatefolds and credits on their sleeves and liners and their cover art, title and artist displayed in the top third because the designers know that’s what you see as you flip through the bins, it’s the same way you walk past faces in a crowd and one catches your eye. To this day when I see Cale’s name on a jacket I wow and flutter, because inside that jacket is more than a stamped disc meant to spin in the background of a chilled-out house party in 1976, lit by candlelight and incense and the aroma of fondue. It’s a hundred man hours of performing in a hand shaped space, microphones placed just right, an engineer sensing and sciencing the final mix. It’s a million sound-hours of storytelling in the world’s ears. It’s the exchange of lives that I have come to call love. And this was my first.

© Brian Sorrell

Brian Sorrell has worked as a cook, typist, computer programmer, woodworker, bicycle repairman, and university lecturer. In February 2012, he and his family packed up their house in California and relocated to Auckland, New Zealand, where Brian writes about life as a stay-at-home-dad at “Dadding Full Time” and life as an expat at “Root Beer in New Zealand“. Visit Brian at Dadding Full Time on Facebook, Root Beer in New Zealand on Facebook, @DaddingFullTime on Twitter, or connect with him on LinkedIn.

Part 5 of an essay series on First Love.

You May Also Enjoy

Brian- I always love your stuff, and maybe this piece explains it. Our musical trail is nearly identical, despite being about 15 years apart. With a dose of Elmore James and John Mayall tossed into the mix. I wore out a vinyl copy of Allman Bros Live at the Fillmore learning all the licks. Ditto for History of Eric Clapton. BTW- I’m still using the Technics SL-23 turntable I bought in1977. Kudos, man, kudos.

Thank you David. You’re speaking my language here with James and Mayall &co. I bought a Technics turntable somewhere around 1987 and it lasted a good long time, but eventually got lost in moves around the world. My wife surprised me with a simply gorgeous Rega RP-1 a few years back on my birthday and it’s one of my prized possessions. We listen constantly. It’s a love that lasts, that’s for certain.

This makes me remember when music meant so much to me. Every time I heard a new song it was if I had discovered it. It was exciting. While I still enjoy music, but generally, the freshness is gone.

One reason that I’ve stuck with vinyl is that the experience of putting a record on helps me feel more connected with the music. It helps me appreciate all that has gone into each song, each expression — so much more so than when I can simply click to the next track, oh so selfishly.

Well composed, Brian! How I wish I had not given a hundred vinyl records of ’60’s – 80’s rock and folk music to my Honors students as presents, not having the presence of mind to save them for another time!

Thank you David. If you have any more of those records you want to offload, I know a guy who’d take them!

Short on time so this won’t be the response you deserve, but it is the one I can give now. When I think about Robert Johnson facing the wall and presence two things jump out at me:

1) The idea that he was trying to play in a way that presented his music in the best possible way for his listeners.

2) That he wanted to focus on the music and not get distracted by the audience.

Maybe this is too self indulgent, but it reminds me of how I write. I could do more to engage with people and market, but sometimes the need to just play/write overwhelms the rest.

And when I think of music I think of stories, texture and layers. I think of storytelling. They are connected, intertwined in a vine that has a massive trunk and endless roots.

Thank you Jack.

This is perhaps what makes your writing feel so intimate so often. There’s always an honesty to what you write, an unfiltered honesty that I appreciate. (And I think Cale would too, judging by a bunch of the other stories I read of his recording techniques. But that’s another story….)

I love this piece of writing, Brian. So many layers. These early passions provide life-long lessons and satisfaction.

Terrific contribution to this series. Thank you!