My mother was beautiful, stunning really – 1940s movie star stunning. She had black curly hair, pearly teeth decades before bleaching and veneers, wide-set hazel eyes, and lush, arching brows that gave her face softness. Her nose was fine, and her full lips were painted deep red, shimmering coral, occasionally pink. She wore no other make-up. Only lipstick.

She smiled easily, and her symmetrical face was a jeweled thing. When she was young, she was impossibly radiant.

It’s hard to explain evil that festers beneath an exquisite surface, just as it’s implausible that beauty shines through a physical image that someone has deemed ugly.

Yet both exist.

Judge the behavior, not the person.

For all her beauty, my mother suffered terribly. I am certain of this, so I try to separate the behavior from the person. If you must judge – judge the behavior.

That I know she suffered does not excuse her, but a sharp tongue lashes out from a place of pain, and apparently, even as a young woman she lashed out. But when you are beautiful, all is forgiven though there is something missing in you, or possibly, something excessive; perhaps a jumble of the two.

By her twenties, from what I can gather from photographs and stories, my mother was suffocating in her own venom, which she turned on herself in rebellion and rancor, in self-medication and armament.

In food.

She grew fat. More than fat. She grew morbidly obese and with obesity she could justify distance, soured dreams, her acid tongue. She could headline as the victim or the vaudevillian in whatever production she chose to stage, alternately hating and loving her audience, filling every room she entered, sucking out all the available air or at least, the oxygen required for her daughter to breathe.

Drama, dreams, drama.

Her performances took place wherever and with whomever she pleased: any stranger might serve as the audience for her exaggerated tales, her booming voice, and disclosed confidences – mine – an act that left me feeling tiny, naked, mortified. She appropriated my habits, my words, my moments shared with her when caught off-guard. She used them all as fodder to keep the fans amused. She entertained at my expense, while I built walls, perhaps at hers.

Backstage, and I thought at times purely for my benefit, there was sobbing and usually in the kitchen. She hid it from everyone, but let it loose when I was present. Her histrionics were a bludgeon to a developing child, and if they were uncontrollable, the fact that I bore witness was simply of no concern.

And then there would be light – an afternoon at the museum or antiquing in the country; gregarious visitors around the dinner table; a trip to the movie theater, just the two of us; scrabble games that led to laughter. Perhaps I only dreamed the hawk that flew into a rage, the predator with its sharpened beak and razor claws, the way the creature dug her nails into my arms and drew blood. Hours later the hawk transformed into the dove, and the dove was beautiful.

Every day.

Every day, coffee. The pot was on more or less at every hour, flowery aprons tied around the big belly with a bow in the back, the occasional neighbor stopping in to chat or gossip and sip.

These were stay-at-home mothers when there was no name for that because it was the norm, just as pot after pot of Maxwell House percolating through a glass bubble in a metal lid was the norm, on the top left burner of the olive stove, in the pine paneled kitchen, where my mother cooked and conversed, studied and read, screamed and sobbed, sat in a stupor and ate. And ate. And ate.

There was coffee, and there were amphetamines. Diet pills. I wonder what part they played in her erratic behavior except there were indications even before the marriage, before the obesity, before the pills so easily purchased, and in the years when she was movie star beautiful, and even then, something was off.

Family futures.

When I was twelve I began to study myself in the mirror – in every mirror – loathing what I saw and no doubt starting sooner than twelve, but unable to remember. There are self-portraits in brown sketchbooks and I must have used a glass to capture my likeness, but the recollections of doing so have evaporated.

There are memories of a mirror and a rug, stretching my limbs to be a better dancer, studying my ill-equipped form for anything I imagined as a viable female future, and my brother who would confirm not only that I was fat but that I was ugly, by telling me so. And I would slam my door, hide in my room, give up eating, walk for miles at dawn when no one knew, and cry. I would cry quietly unlike my mother who sputtered, red-faced and ranting, sobbing and heaving, demanding the spotlight for her suffering and in so doing, causing suffering hidden in the shadows.

I was doomed to be obese like my mother, or so I thought, but without her beautiful face that still drew so many to her outrageous storytelling and magnetic presence, a presence she could turn off and on blithely until the days when she began to crumble in on herself.

As for the twelve-year-old who fears she will become her own worst enemy, the child who cowers at the mean-spirited remarks of another, the voice that grows smaller and eventually silent, sadly, there is nothing so unusual in this scene. Siblings can be cruel and they outgrow it. Eventually they apologize, and I have a vague recollection that my brother did so, twenty years ago, and then he grew cruel again and drifted out of my life. But that is a set of chapters for which there is nothing but the blank page.

It takes two hands to hold the mirror steady.

My questions about those years persist. Why was every day of my brother’s life in that house so different from every day of my life in that house? Why were my brother’s accomplishments his own, his comings-and-goings unmarred by my mother’s twisting? Why were my words, my ambitions, my achievements all hers for the taking?

There is a wise man who helps me hoist mirrors, who assists when I sense a need for variations on the truth, who reminds me how to see the truths of the woman who gazes back.

Extra hands are useful. Extra eyes promise perspective. Shadows distort our vision.

As does time.

I have taught my sons to hold their mirrors with a strong grip, and then spin and spin and feel how dizzy they become, and realize how the view of their surroundings flickers and blurs, disassembles and comes together again strangely as they catch themselves in each others’ reflective light. So they laugh, spin, grow dizzy, fall, get up, spin again, and drop to the floor and sprawl in a state of happy excitement that tells me something in this house is very right.

They rise smiling to see the many faces and understand: there are fragments that jut and shuffle and reconfigure. There are approximations. Pieces of a puzzle are not the puzzle.

There is a special candle and I cannot find it.

The candle I light for my mother is makeshift; I cannot find the one I purchased for this occasion so I settle on a tea light placed in a glass votive holder. When it burns out I will light another, and another, and another if needed until the twenty-four hours have expired.

My gods will not mind; they are giving and colorful. The god of my mother was vengeful and one-note. She let loose her god and together they stole and hoarded until I put an ocean between us, giving myself a new tongue and a new name, as well as my given name in a new tongue.

It is a strong name. I am a strong woman, though I do not claim to be beautiful.

My mother chose the wrong gods.

Humanity.

Four years ago I fell in love with a devout Catholic who lives in Normandy, a man who carries his faith without need to proclaim it to a crowd, a faith he handles with tenderness. I am enamored of silence; inner conversation may flourish without interruption, and so my lover’s quiet made room for me while his Catholic god made space for an adjacent faith. We once attended mass together at Christmas, in a church near the square where Joan of Arc was burned at the stake.

The priest spoke of men and women taking care of each other in a complex world. He preached a rousing and intelligent sermon that would have served any variation of named gods with equal effectiveness. Yes, named gods. After all, we create names – and we bestow them on our gods because we use language for what we see and cannot see, for ideas and objects, to distinguish one person from another, and in ways that inch closer to truths more vital than occupations and lineage and titles.

When we see each other, when we smell each other, when we taste each other, when we hear each other, when we touch each other – even if we peel each sense away and subtract sight, smell, sound, taste, touch from the mix one at a time, we still know those who are close to us. We need no names.

But we cannot see our gods, or smell them or taste them or hear them or touch them – though some would say otherwise. Perhaps this is why we are compelled to give them names and lay claim to ownership. Some of us are accustomed to forgetting our nouns; we are reliant on dreams and alchemy to fill in the blanks until they return. We do not need to name our deities, and we do not know enough to name our demons.

In that church, at that Christmas mass, we sang – hundreds of voices in harmony, bodies pressed together as we crowded onto pews, the cool of my lover’s long fingers wrapped around my tiny palm, and this became my holy land: a populace of whisperers, language that flourishes in soft voices, silences that pose no threat, nights when we prefer to sing.

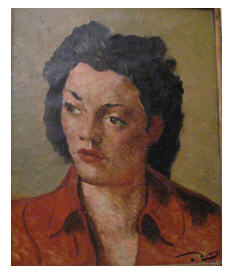

André Dérain painted her twin.

That holiday, I visited the city’s museum and came across a luminous painting by André Dérain. He was known as a Fauve – one of a group considered “wild beasts” – producing artworks that reinvented our way of seeing, and feeling what we were seeing. The small oil I viewed dates to a later period. I’m guessing the 1930s. It is a portrait, and the face is beautiful – not quite movie star beautiful, not quite the 1940s eyebrows – but with her dark curly hair, her deep red lips, her wide-set eyes, she bears a remarkable likeness to my mother.

That holiday, I visited the city’s museum and came across a luminous painting by André Dérain. He was known as a Fauve – one of a group considered “wild beasts” – producing artworks that reinvented our way of seeing, and feeling what we were seeing. The small oil I viewed dates to a later period. I’m guessing the 1930s. It is a portrait, and the face is beautiful – not quite movie star beautiful, not quite the 1940s eyebrows – but with her dark curly hair, her deep red lips, her wide-set eyes, she bears a remarkable likeness to my mother.

Why did my mother never learn to hold the mirror steady? Why did she never ask for extra hands? Why was this tortured, brilliant, violent woman never able to possess her own beauty, to name a different god, to address her demons – or at least to contain them?

Mirrors are heavy.

Some mirrors are gilded. Some are silvered and hazy. Some are fun house mirrors and we anticipate the distortions – the lengthening and the dwarfing. We chuckle or giggle or chortle or guffaw; we stare and study and pose hypotheticals; we move on to the next amusement.

We know mirrors for what they are – trickery.

We are all vain, at least a little. We need our reflections as reassurance. Sons and daughters peer into mirrors, though sons raised by mothers, less often than daughters. They do not fear the figure that stares back; the blurring of boundaries does not the haunt them through their sex.

And now for the lesson in parts of speech: sons are trained as verbs, with freedom to act. Daughters are cultivated as adjectives, with the purpose of qualifying.

When daughters do not grow into their beauty as expected, they disown their adjectives and lay claim to verbs.

And so we inherit language or invent it, we stroll into it or adopt it. We ignore it or we draw confidence in its usage and competence in its economy. We wrestle it, we conquer it, we negotiate with our own spinning.

I have thrown these words together quickly; I owe them better – time and tightening. But I have neither on another night of insufficient sleep. Nonetheless, I will sing my rebellion: no to history, no to forced grammars, no to one-note gods of a single name and a single view of truth. I will muster verbs in two languages, master what I choose, and choose what I master in the name of a woman who is strong, but who needs no name to lead her charge.

I am fortunate that my two working hands still hold the mirror steady. And there are others to help, when I can no longer shoulder the weight. I may spin, grow dizzy, fall down, climb up, and spin again. In this, I see the many faces. They are pieces, not the puzzle.

You May Also Enjoy

Reading your posts is like being submerged in warm honey, even when the subject matter is heart breaking.

You write: “I have thrown these words together quickly; I owe them time and tightening, but I have neither on another night of too little sleep.”

I respond: Your words are exquisite and powerful. Reading them often intimidates and awes me.

I agree with Kelly, your words are “exquisite and powerful”. I wish I had something to add to that, but I’m awestruck (once again) with your honesty and insightful words about the dangerous beauty that was your mother.

Exquisite and powerful indeed. Your last few posts have left me feeling both full and empty in the best possible ways. I feel like I am getting to know some of the deepest places of you, and yet now I have so many more questions.

I love this passage: “I will sing my rebellion. No, to history. No, to forced grammars. No, to one-note gods of a single name and a single view of truth. I will muster verbs in two languages, master what I choose, and choose what I master. In the name of a woman who is strong, but who needs no name to lead her charge.” How does it make you feel to be such a master (mistress, I suppose?) of language – of verbs, nouns, and, yes, adjectives too? No forced grammars for you. That’s for sure.

Yes, you have verbs. And even though nouns try to escape you, you find a way to grasp them. Maybe not in the way you’d like or in the easiest way. But you do it. And then you build your own unexpected adjectives.

Really, I have to walk away now and sleep.

Hearing, touching, smelling, visualizing… your words mingle and coax, they jab and they lap. And then, this post left me engulfed in wordless raw emotion, dropped into a glimpse of places you have been.

After awhile, I thought of Ingmar Bergman, whose father locked him in a closet and told him a monster lived there who would eat his toes. I think of anguish and anxiety, love and sensuality, fear and obsession shaping the psyche of the artist.

Then I thought of Exodus (38.8), where Bezalel, crafting the sacred space, or Tent of Meeting, “made the laver of copper and its stand of copper, from the mirrors of the women who performed tasks at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting.” Something about turning tools of vanity into a vessel for the sacred wove through my mind along with your evocation of mirrors.

Your writing inspires, as it redeems pain and renders suffering productive, fertile, luminous—a vessel of the sacred.

Another amazing post. You draw us into your heart from many different perspectives. This is writing at its most perfect.

As many have said before me, exquisite and powerful. I feel as I read what you write. Invoking feelings in readers is the one thing, as a writer, that I fear. You have taken us into your heart, your mind, your soul and let us see through your eyes.

Your writing is so rich and so beautiful and evocative and heartbreaking and inspiring. Really. I am sitting here, drinking my coffee, as my toddler looks at herself in her toy mirror beside me. Can you believe it? It is if I was meant to read your words now. Right at this very moment. And to stop. Consider this toy. Why a mirror? What does she see? What will it mean for her as she grows up? And how will I help her to hold it steady, teach her to spin it around like you did for your sons? There is so much to your writing. I wish we could sit down and have a conversation.

For you, it is the reflections in the mirror. For Cambodian children before the Khmer Rouge took over my country, it was form playing in the sand on the banks of rivers. they would sit in a cirlce and take turns lying in the impressions in the sand made by each otherr’s bodies.

This is a powerful and complex post. The dynamics between mother/son and mother/daughter seem to vary greatly as you say “Sons are raised as verbs, and daughters are cultivated as adjectives.” I think mothers often live through daughters and if they don’t live within their control they try their best to manipulate them… not always, just some mothers which your mother sounds as if she did. I like the way you use the mirror analogy and end with this ” In this, I see the many faces. They are pieces, not the puzzle.” I think this is an essay I will be thinking long and hard on for a while. I think this is one of the most beautiful and provocative posts of yours I’ve read. It is filled with heart and soul, bittersweet.

Thank you. Reading your post today, I thought of this, written on the anniversary of my mother’s passing. You have such lovely memories of your uncle.

WOW. I am in awe of your writing. It both fills me with hope yet at the same time a profound sadness. I hope you don’t mind me saying this but it sounds like your mother may have been bipolar. I have a sister who has been diagnosed as such and your description of your mother is very reminiscent of her. I am so sorry you had to go through that type of upbringing. It’s awful when you never know which person the one you love is going to be at any given time. Very heart wrenching.

Thank you, Peg. I won’t ever know what the issue or issues were, and she may have been bipolar. And of course in the 60s, diet pills were plentiful, and I imagine that worsened things. But there was something more, and whatever it was I’ll never know, but I was the target. It continued until the end of her life. Enough time has passed that I can acknowledge the good she gave me, but some wounds never heal. It is what it is. And it taught me to parent very differently.

Thank you for sharing this link with me. I agree with Peg. It sounds like your mom suffered from an undiagnosed bipolar condition. Very sad because it affected you in ways I’m sure you are still discovering. I once said to Trisha at Hadassah Speaks that one cannot truly find peace until they find all the pieces. I understand why you embraced that Christmas in Normandy. The unconditional love you felt with him, at that church, on Christmas, was something you really needed. So many lessons to be taken away from that moment.

I hope and pray you find all your pieces and can successfully fit them together into the puzzle called life. ~Peace to you, my friend.

After all that you can still light a candle for your mother? What a woman you are. Relationships with mothers are complicated. Mine is too. Not on this order of magnitude, but complicated nonetheless. I hope this touching reflection brought you clarity. I suspect this is the kind of murkiness that never fully clears. But I still wish that for you.