When my giggling four-year-old runs over to me with a scribbled blob of paint on construction paper, yelling “look, look!” and I instinctively ask him “what is it,” his grin fades and he stops giggling. He has to think about what to say. He isn’t excited about what it is. He’s excited that it is.

When my giggling four-year-old runs over to me with a scribbled blob of paint on construction paper, yelling “look, look!” and I instinctively ask him “what is it,” his grin fades and he stops giggling. He has to think about what to say. He isn’t excited about what it is. He’s excited that it is.

*

Recently I read an old essay by Susan Sontag, the titular piece from her collection “Against Interpretation.” In it I found a perspective that has improved my parenting. She writes: “Interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art.” It’s a bit of an odyssey to explain how I get from art to parenting, so I’d like to chart the journey, here.

First, I should explain that Sontag was a maddeningly articulate figure, and reading her essays reminds me of my former academic life in which we all thought “getting it” carried an air of exclusivity, holding leverage over those who don’t. Reading the essay, I thought: How often do we take this tone with kids before we hear their stories?

Sontag talks much of abstract art. She notes deliberate attempts by some artists to obscure content to a point where only form remains. Look at, say, a red canvas with a thin orange line struck horizontally across the middle. What does it mean? What radical expression lurks behind that line? Perhaps the answer is “nothing.” And so what if it is?

It seems to me I’ve been asking too many questions lately and at some point, enough is enough. I’m learning that interpretation is no prerequisite for appreciation. I can thank Sontag, and my son, for that.

*

I’m taking a trip to the Auckland Art Gallery, first by ferry from Devonport, where we live, across the harbour to the central business district. I step out of the ferry building, which looks squatty with high-rises sprung up all around, knowing it once was the most imposing structure on the skyline, back when gentlemen wore hats and tram cars ran through the streets.

I exit the building with the crowd and wait at the crosswalk with business men and business women and tourists in their polo shirts and camera straps. There are students with their portfolios and good haircuts, and an aging rock ‘n roller in his flat front cowboy hat, and threadbare denim jacket and crocodile boots. The light changes to a green walk signal, a starter’s gun, firing our race across the city in all directions.

I follow an elderly couple holding hands diagonal to the west side of Queen Street and lose them when I cut through Britomart train station, smelling of sweet Subway sandwiches and diesel fuel. The space is a contradiction: cold stainless steel chairs in a warm glass atrium. Here are some of the tourists with their large-lensed cameras, and the college students with their pink hair and takeaway coffee, the bankers and the professors and the rough-sleeping anarchists. I am the writer in their mix now.

I can’t understand a word of the announcement over the public address system, too cavernous a space for the mid-range tones of a human voice, sounds bouncing off every wall and window and the corrugated lift shaft.

The sound fades as I cross the door sensor and a glass wall opens. A fierce wind cuts across the station and ruffles my notebook pages.

I walk out and circle the round tile fountain by the taxi stand, heading right down Commerce Street, and crossing just outside the American embassy. The next block over is a gentleman’s club and brothel loudly advertising free entry through lunch, not the same sort of business as a government office, but bustling just as well. I continue past a couple of shuttered fast food lunch spots and backpacker hostels and street prostitutes. The sun cuts across Commerce Street and lights up the white lines between the delivery trucks and sports cars. I walk under an awning shading the path with advertisements for gift shops, gambling rooms, and yoga studios. I cross through a day parking lot with an exit to Shortland Street. I have never walked to the top of Shortland, so I decide this is the perfect time.

Here is a higher end. Real estate headquarters, thirty nine stories of offices, top cut clothing boutiques, investment banks, empty cafés with irresistible midday specials. It’s a location full of professionals and it’s the setting of a soap opera, yet the gentlemen still don’t wear hats.

At the top of the street is a flash car rental, a Kiwi Post, and a swanky art gallery. I take a split in the road up and around another hill and I lose my sense of the places and people, and I start navigating by feel, following the volcanic terrain, up, up, interminably up it seems. I stop to lean against a machine that dispenses parking slips, taking a few notes, remembering on paper, and a woman stops to say “You’re writing an essay. I can tell.”

I make a right turn toward the university, which I recognise from all the trees and old buildings. Immature trees are cut into the foot path and cars cross from out of parking garages. The trees ahead and to the right must be Albert Park, I figure, and so it is. I enter and just inside the gate is a garden clock that’s been there since 1953. The time is set correctly. The sun is high.

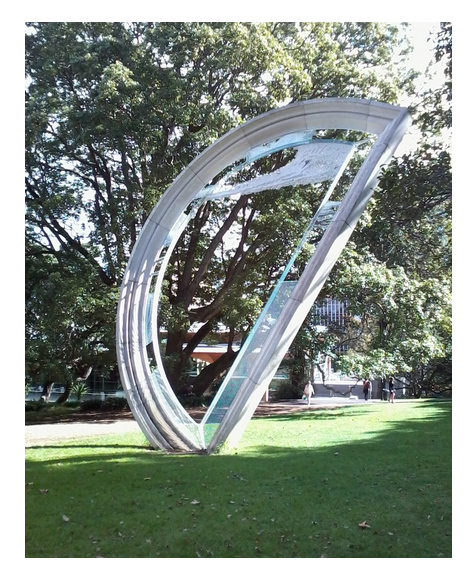

I follow the paths to a sculpture that I know can be seen from the second level garden of the art gallery. It is a line and a curve jabbed into the ground in a D shape. A landmark. I think: “I wonder what that is?” But then it occurs to me: It’s a line and a curve jabbed into the ground in a D shape. Full stop.

I have arrived at my destination.

*

In the distance, the university bell tower chimes. Groups of nondescript people bask in the sunny breeze at the top of a volcano in the central city. Autumn’s closing in.

The Auckland Art Gallery is free to the public and I enter through the café patio to the mezzanine level where piles of large cardboard tubes and boxes had been scattered for kids to build with. Blocks bigger than the children themselves. The sun cuts through the atrium and casts long shadows of the preschoolers’ sculptures against a wall beyond the main staircase. Someone ought to chalk outline the shadows and curate it as an exhibit of shape – “Shadows of Youth” (Various Artists, 2014). Instead, parents and caregivers take photographs that they’ll later share on social media and muse about what the kids meant to build, as if they were doing anything but enjoying the process of setting one block on top of another.

My mission: quit trying to find content in forms. See the form as content – the colour as shape.

This is no easy task, especially given my academic training as a philosopher, where “meaning” is deified to such a degree that we trot out theories of it and worship the most purely rational results.

In my line of vision: A broom of fibre optic bristles attached to a wall, head up, facing out with a spectrum of light oscillating through the tips. I laugh quietly. How entertaining it might be to sweep with it. (Is this an interpretation, or am I simply happier for having seen such a form? Is this what I’m looking for? Is a search for feeling a betrayal of my goal?)

I read about the artist. He was a custodian. He used to sweep galleries, not exhibit in them.

Next I study a pile of discarded metal objects welded together into a clump. My gut reaction: “I don’t get it!” Ah, the intellect eking out its revenge again! Here are objects given new, unexpected shapes. I squat down and watch the outlines of the form against the white wall behind. Then I stand up and the contours move, shifting against the parquet floor. So many ways a thing can be what it shouldn’t be. A basket. A scarf. A fluorescent lamp.

In form alone you perceive materials and shapes, not objects. More and more, I feel a release from interpreted, rationalised life. I like it.

Now I’m standing in front of a white square surrounded by red and grey rectangles. Acrylic on canvas. Not an object, it is objectively meaningless, yet form-full.

There is more: An angled grid of rectangles, beige, some cut into triangles, black and red; a crisp painting of a machine, beautiful in its way, from the middle of the twentieth century, a portrait of a machine; a painting titled “Samoan Woman In Yellow” (1954), mostly triangles, golden yellow, solar yellow, dusty yellow.

I am amazed at how much a triangle can achieve. And I wonder how joyful might it be to look at a portrait without asking “who is this?” So I do. I trace back to my pre-interpretative impressions. She is a Samoan woman in yellow. She is a collection of triangles. She is oil on canvas. She is inspiration. She is beautiful.

That is enough.

*

Later in the day I pick up Noodle at kindy and as always he has a new painting in his bag. I ask him, “What is it?”

Ack! Haven’t I learned my lesson?

He struggles to tell me, because it isn’t anything. It’s abstraction. It’s technique. It’s a shape, no interpretation needed, no tyrannical correct response.

I back off the question, and wonder. What benefit will either of us realise if he answers?

I change my approach. I ask: “Did it feel good to put paint on the paper?”

“Yeah.”

He brightens, same as when I put words on paper. Then he says “and we hung it up on the rack and it dried and we built a school.”

“Built a school?”

“Yeah.”

Brighter still. “I said we need a big boy school coz I’m a big boy!”

And he tells the story of arranging the large wooden blocks and the plastic dinosaurs and how his two best mates got involved and they built a gate so the animals wouldn’t get out – the animals? Then they rearranged the toys and cars they had brought over and lined them up for no other purpose but to appreciate them as a line. They counted out the cars… one, two, three… and named their colours. They vroom vroomed them around and around. They gave them sounds, voices, stories.

The teacher tells me Noodle asked her to help round up the animals and put them in the new big boy school he built. While she helped, she asked him “do animals go to school?” She said he stopped and thought about it for a minute, and you might as well have asked him for the meaning of life. But he gave the right answer, I reckon. He told her quite simply “well, they do today.”

And that is enough.

© Brian Sorrell, text and images

Brian Sorrell has worked as a cook, typist, computer programmer, woodworker, bicycle repairman, and university lecturer, all of which inadequately prepared him for his current full-time role as Dad. In February 2012, the family packed up their house in California and relocated to Auckland, New Zealand, where Brian now specialises in chasing his always-on-the-run son, drinking coffee, and recording his adventures at “Dadding Full Time.” Visit Brian at Dadding Full Time on Facebook, @DaddingFullTime on Twitter, or connect with him on LinkedIn.

You May Also Enjoy

Oh, I absolutely loved this. Brian, I hope that you will write here often. While I am not a parent, I so appreciated your shift in focus and the experience that took you there…plus, anyone who calls their kid Noodle is ok by me. 😉

I also was grateful for the reminder to like what you like without naming it. It drives me crazy here in France – it is always about the “why” or “social context” – I can talk that talk if I need to, having self-educated myself during over ten years in Manhattan where I would go to see something artistic several times a week but I would really prefer just…to enjoy.

With my Best Wishes from Provence,

Heather

Love this. We all struggle with “What is art” to us.

Beautifully composed, an art installation piece of your own! More please!

Though my mother was an artist, hers was very (go away and google) figurative (the opposite of abstract). I haven’t had much exposure to other types of art until middle age. In working with my own craft projects I get huge pleasure just from the colours and textures of fabric, whether or not I manage to make anything pretty or functional; for me the process has meaning (though I do prefer a functional outcome). I’m afraid I’m not particularly artistic, being tyrannized by my left brain.

Gorgeous storytelling as usual- love every line and the pictures your words paint. 😉

Brian,

Thank you so much for this eloquent piece of writing that encourages me to see differently – and to continue requiring myself to feel rather than to simply “see.” And thank you for sharing your storytelling talent with us here. I hope you will again. It’s been pure pleasure.

Oh the wisdom and delight and innocence and absolutely spontaneous wisdom of children. I loved this, Brian! Is interpretation a prerequisite for appreciation? Such a thought provoking question. This was a delightful, artistic meander of a read. Love, indeed, is the best interpretation. And it’s enough.

Hi Brian, Very transporting piece—really enjoyed it. I’ll share a memory it evoked: I used to live in New York, on Thompson Street, when I was in film school preparing for what would later turn out to be a future career in psychology. I often ate at a little unpretentious sushi bar down the block and one time a friend who was dining with me leaned over and whispered, “That’s Susan Sontag over there…” I had not read her, and still have her on my list to read, but not yet; however, now that I knew it was her, I often saw her eating there alone, usually Sunday early evening, I was usually alone on Sunday too, it was the mid 80’s before I’d met my wife, before Susan had met Annie Leibovitz. I never said a word to her, but I watched her form, me an aspiring artist with grand ideas and she a legend even though I knew only that.