A Stolen Life

In 1946, Bette Davis played a dual role in A Stolen Life, the story of identical twins with very different personalities. It’s a melodramatic film, predictable yet thoroughly enjoyable, and it’s one that has always stuck with me.

In 1946, Bette Davis played a dual role in A Stolen Life, the story of identical twins with very different personalities. It’s a melodramatic film, predictable yet thoroughly enjoyable, and it’s one that has always stuck with me.

I imagine it is a desire to call upon my own evil twin, to give voice to the fact that I harbor a sense of a life I do not lead (that I should have?), and stubbornly hope – like many of us – that I’ll manage a taste some day, after all.

And who hasn’t fantasized about inhabiting another person’s world, even for a short time – especially if that world is more glamorous, more fulfilling, or simply less restrictive? Who wouldn’t love a twin to enable you to escape yourself, to find yourself, to be yourself or not yourself – and get away with it?

Good girl, bad girl

The plot is classic: one sister is plain, sweet, and self-sacrificing; the other is selfish, manipulative, and seductive. I adore this metaphor in twinning – the opposition of good self-bad self, and the freedom the “bad self” possesses in comparison to the one who is constrained by conscience and scruple.

Hollywood-style, the good sister falls in love, and the bad sister steals her man and marries him. When the nasty twin dies in a boating accident, the “good” sister appropriates her life, believing this impersonation to be her one shot at happiness. Naturally, our heroine has no clue of the complications inside the marriage, not to mention a collection of unsavory characters she is ill-equipped to manage.

As for the lessons in this tale?

They are many, and they unfold as anticipated. Good girl versus bad girl, integrity versus deception, what you see is not what you get, and none of us can know what really takes place inside a relationship. Or is the message something else, from a place of contemporary reflection? To be successful, you must be beautiful? To be successful, you must be daring?

The Mirror has Two Faces

Who hasn’t wanted an identical twin, at least as a child? A way to split oneself into two, even if only to pull off pranks like those in the 1960s sitcom, The Patty Duke Show? Wouldn’t it come in handy in adulthood – this ability to offload our problems to a look-alike self who could advance our causes more readily, without emotional burden?

Or better still, how glorious to hand over the reins to another version of self, one who is tougher, smarter, sexier, and more successful – even if more ruthless?

In 1958, a French film, The Mirror has Two Faces (Le Miroir à Deux Faces) offers a different take on this theme. While not the story of twins, it is a tale of perception and potential. A plain, middle-aged woman enters into a marriage of convenience, and when given the opportunity to transform herself through plastic surgery, her husband refuses to allow it. She undergoes the cosmetic procedures despite his protest, and when she is beautiful, he rebukes her.

In 1958, a French film, The Mirror has Two Faces (Le Miroir à Deux Faces) offers a different take on this theme. While not the story of twins, it is a tale of perception and potential. A plain, middle-aged woman enters into a marriage of convenience, and when given the opportunity to transform herself through plastic surgery, her husband refuses to allow it. She undergoes the cosmetic procedures despite his protest, and when she is beautiful, he rebukes her.

Would we risk that, for another self we might want to explore? The loss of security, familiarity, and one dream of potential for another? Who hasn’t looked in the mirror and examined her face – not only to search for a younger self – but for a stronger self, a better self, a more liberated self?

Meeting our twin

As children, we are raised with codes of right and wrong, notions of actions and consequences. Some of us learn our way around the rules; others excel at breaking them, and getting away with it. For those schooled in a rigid set of principles and well-conditioned to follow them, wouldn’t a little bend serve us better? Who wouldn’t want to dip into the arsenal of one’s own evil twin, to exact justice – or, as in A Stolen Life, “to find a little happiness?”

Can we discard the guidelines of childhood, to learn from meeting our own (evil) twin? A more adult and pragmatic version of who we are?

Moral lessons, Women’s issues

Of course, in A Stolen Life, we are delivered an era-appropriate morality tale (“the truth is the only way”). The good twin is ultimately rewarded with love, when she reveals her true identity.

But moral lessons on screen or in fiction are rarely the stuff of real life. Men and women do battle. We fight each other and ourselves. We engage in hand-to-hand combat with ghosts and shadows – of parents, of siblings, of lovers, of ex-spouses. The reasons may blur, but the behavior takes on a life of its own. I wonder about origins, about the measure of transference from another time, or another place; the adversarial evil twin – in our enemies, and in ourselves.

A desire to twin oneself is not the fantasy of cloning. In the case of the latter, we are desperate to stretch our days beyond their 24 hour confines. Our plates are overflowing, our schedules are unrelenting; we need more bandwidth to tend to everything that we must – and at least a little of what we would like.

The fantasy of a twin is another matter: we desire to step in and out of a different self, a broader self, a spectral self, a freer self.

A self in opposition to whatever daily posture presents as our norm.

Perhaps in this fantasy we search for more good in ourselves, more bad in ourselves, more bravery, more audacity, more brains, something lost or insufficiently nurtured. Perhaps we seek to pick through the tenets of acceptable behaviors, to grow up and grow into the vast expanse of gray that shifts and ripples between black and white. We seek to accomplish our ends, through different means.

Especially when Bette Davis flashes across the screen in the middle of the night, and we imagine a stolen life, a legitimate life, a different life – knowing we all wear masks, and our mirrors have two faces, if not more.

Bette Davis image, 1950, All About Eve, public domain (Wiki)

Le Miroir à Deux Faces, image via Tout le Ciné; click to access original.

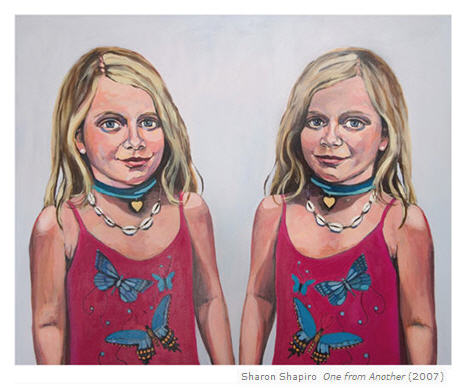

Painting by Sharon Shapiro, reproduced with permission of the artist. Click image to access her site.

© D A Wolf

And there’s the “child’s” version, like the young twins in Parent Trap switching places and conspiring to reunite their divorced parents … another example of “twinning” providing perceived happiness, this time for more than the twins themselves. (And an opportunity to hear Hayley Mills sing, of course.) =>

I used to pray every night for my real parents and twin sister to find me (you know, because I was somehow switched at birth and totally didn’t belong in my family). In my heart, I just knew that meeting my twin would connect me to myself and show me that there’s a place I belong. I definitely think the concept of twinning is about being whole, about two sides of the same coin, and how we so often feel like that other crucial piece is missing.

I love psychoanalyzing movies! Many of them mimic life and always provide us with a glimpse into our cultural soul. A thoughtful post.

I love some of these old movies! Having seen many of them for the first time as a kid or teen, on TV, they touch on memories as well. (And there are so many other great twin movies – happy ones, creepy ones, psychological thrillers.)

My life is complicated enough without a twin to worry about! ha. Nice post. I’ll have to see the movie sometime.